Happy Birthday, Julia Child

It was one of those circular email

letters: the ones that come from lovely websites that you sign up to in a

moment of enthusiasm... Usually these messages from Epicurious (http://www.epicurious.com/ ) are about

gorgeous recipes that are far too complicated for me and that I can’t afford

the ingredients for anyway. This one got my attention, though: advertising the

fact that August 15th 2012 is the centenary of the birth of Julia Child. She

was the greatest cooking guru ever - nothing

like the self-proclaimed experts we get on TV these days. A lady who had

standards. She was one of the first writers to reveal classic French cooking to

the English-speaking public. Her recipes are real cuisine, not those icky,

much-handled little piles that posh nosh places serve up today. She’s a household

name in America, where she grew up, and there’s a recent film about her life: Julie & Julia. It's also about a

blogger who cooked her way to sanity, and incidentally fame and fortune, by

working her way through Julia Child’s classic cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Meryl Streep plays Julia. I'm

not wholly a fan, but she’s excellent. And it was the blogger’s story that encouraged

me to have a go at blogging, so I've got to celebrate the anniversary! No way

can I devise a cake recipe to Julia’s standards, as Epicurious suggests, so

instead, here are some of the food-related gems I've found in the RGSSA’s

catalogue.

The Art of Living in Australia?

I've no idea why the Royal Geographical

Society of South Australia has this treasure - possibly someone was misled by

its title. It’s not a sociological study, or an “immigrants’ manual” (a popular

genre of the time), it's a cookbook! In fact, one of my favourite early

Colonial examples of the type; I knew it long before I found out the RGSSA

holds it:

Muskett,

Philip E. and Wicken, H., Mrs

The

art of living in Australia / by Philip E. Muskett ; together with three hundred

Australian cookery recipes and accessory kitchen information by Mrs. H. Wicken. London : Eyre and Spottiswoode, [1894]

You can download a copy from Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/4219. Today,

although that was not its purpose, it does gives us an interesting picture of

the habits and commonplaces of the Australian way of life at the period. It’s

fascinating to see which dishes have survived well into the later 20th century

and even until now – though in some cases as commercial products rather than

good home cooking – and which have fallen by the wayside. Like all the cookery

books of its period it relies heavily on those that went before it, and so we

can see the influence of Mrs Beeton, but without all her table embellishments.

It is determinedly middle-class, as the cookbooks of the period were: if all

housewives were still not expected to do their own cooking, in the colonies

many did, and at the least they were closely involved in supervising the

kitchen. The recipes are for the most part quite practical, and still useable

today. Mrs Wicken’s approach, in fact, is in strong contrast to the pompous,

dictatorial and sometimes hectoring tones of Dr Muskett! Post-Mrs Beeton most

cookbooks in English were written by women, and he only tells us what to think

about food, not how to cook it. Here he is on “Abuse of tea by the gentler

sex”:

“The

gentler sex are greatly given to extravagant tea-drinking, exceeding all bounds

of moderation in this respect. Many of them, moreover, live absolutely on

nothing else but tea and bread and butter. What wonder, then, that they grow

pale and bloodless; that their muscles turn soft and flabby; that their nervous

system becomes shattered; and that they suffer the agonies of indigestion?

Their favourite time for a chat and the consumption of tea is at any period

between ten o'clock in the morning and three in the afternoon. Now, if there is

anything of which I am certain, it is that tea in the middle of the day, say

from ten o'clock to three, is a deadly destructive fluid.”

|

| Ladies ready for tea in Australia, 1880-1890 (From an original photo in the State Library of Queensland) |

Muskett isn’t

wholly opposed to tea drinking: he does allow it to be drunk judiciously: ”It should rather be looked

upon as a delicate fluid to be imbibed only in very small quantities.”

Afternoon Tea & The Alien Corn

Amazingly, two recipes for teacakes got

past Dr Muskett! Well done, Mrs W.! Or did the good doctor perhaps fancy a

plate of buttered teacakes, himself? These two demonstrate an interesting stage

in the history of the teacake in Australasia. One version, which Mrs Wicken

attributes to Yorkshire, rather than giving it as her basic teacake recipe, resembles

the traditional English teacakes. Teacakes (earlier “tea-cakes” or “tea cakes”)

were originally small muffin- or crumpet-like flattish yeast cakes, meant to be

served hot, buttered. The classic recipe, as given by Mrs Beeton, is a yeast

dough without dried fruit, though she offers the addition of currants as an

alternative. Later versions usually incorporated dried fruit, and with the

introduction of baking powder, used it or self-raising flour. They were an

afternoon tea dish: never mind old Muskett’s objections, the habit was already

well established here! This is Mrs Wicken’s basic version:

Tea

Cake

1 lb. Flour--2d. 1/2

pint Milk--1d.

2 oz. Butter--1 1/2d. 1

Egg--1d.

2 teaspoonsful Baking Powder 1 teaspoonful Sugar--1 1/2d.

Total Cost--7d. Time--20 Minutes.

Rub the butter into the flour, stir in the sugar and baking

powder. Beat up the egg and milk, and mix the dry ingredients into a dough with

them; divide into two pieces and form each into a flat cake. Cut lightly across

into four with a knife, put on to a buttered tin, and bake twenty minutes. Cut

open, butter, and serve.

(Mrs Beeton also says you eat teacakes fresh, hot, but adds:

“but, when stale, they are very nice split and toasted.”)

|

| Keen cooks still sometimes make their own teacakes: they usually seem to be eaten toasted today |

Unlike scones, these plain teacakes have

not survived into the standard modern repertoire, though similar recipes (often

not nearly so clearly written) would reappear in the unspecialised books until

about 1950. We can see that baking powder - much more convenient and less

time-consuming to use - has replaced the traditional yeast, here. It had

already come in in Mrs Beeton's time, just over 30 years earlier, but her

recipe still uses yeast. Over the next few years teacakes became sweeter. Their

place has largely been taken today in Australasian cuisine by sweet American

muffins, which are readily available commercially.

The foundation of all baking at the

time The Art of living in Australia

was written was, of course, white flour. Australia had been producing wheat since

the early days of European settlement: there are several items in the RGSSA’s

collection on wheat growing and milling, including a curious little offering by

F.B. Guthrie from the Agricultural

gazette of New South Wales, 1901: 28 pages on The history of a grain of wheat.

The Goddess Pomona

Pomona was the Roman goddess of fruit

trees. She had lots of suitors, so the story runs, including Pan. It was

Vertumnus who seems to have been most desperate to win the luscious lady,

wooing her disguised as a reaper, a grape grower, a fisherman, and a soldier,

none of which worked, which when you think about it, they wouldn’t! He finally

dressed up as an old woman and talked her into accepting him in his proper

form: the god of gardens and changing seasons. Well, you can see that that

might ring a bell with the fruit goddess. A remarkable early fruit-related item

in RGSSA’s collection, a real hymn to Pomona, is:

Langley,

Batty, 1696-1751.

Pomona,

or, The fruit-garden illustrated. : Containing sure methods for improving all

the best known kinds of fruits now extant in England. Calculated from great

variety of experiments made in all kinds of soils and aspects. Wherein the manner

of raising young stocks, grafting, inoculating, planting, &c. are clearly

and fully demonstrated ... London : Printed for

G. Strahan; R. Gosling, W. Mears, F. Clay, D. Browne, B. Motte, and L.

Gilliver; J. Stagg; J. Osborn; and C. Davis, 1729.

|

| Pomona, Plate XVIII (Some cherry varieties) |

Batty Langley

(he was named for a family friend, poor guy!) was an eminent English architect

of the period when the Classical influence was all the rage and they were all competing

in the Palladian stakes to outdo Palladio himself. Most of his published works

contain detailed illustrations of the most monumental kind, including one

effort which tells you how to de-Gothic your genuine Gothic architecture! Help! One gets the impression from

those very grand tomes that he must have been one of the greatest stuffed-shirts

that ever walked, but actually, this volume on fruit growing gives one pause:

maybe he was a keen gardener as well, and, if undoubtedly carried away by the

glories of Classical architecture, did a lot of what he did in order to please

his noble clients. Well, I like to think so. His Pomona, unlike his architecture, is not Classical or grandiose. The

plates have got rather dark over the years but they're still lovely. I think he

really did love gardening and especially raising fruit. Though only the richest

of his noble clients would have managed to raise table grapes in England!

|

| "Black Esperione Grape". Plate XLV from Pomona |

The name “Pomona” derives from the

Latin pomum, meaning apple or fruit:

it is also the root of the French word for apple, pomme. Mrs Wicken’s nicest recipe using apples is:

Apple

Fritters

3 Apples--2d. Frying

Batter--1d.

Hot Fat; Sugar; Lemon--1d.

Total Cost--4d. Time--5

Minutes.

Peel and slice up the apples into rounds, take out the core with a

small round cutter. Make frying batter by directions given elsewhere, and

flavour with lemon juice.

Dip in the pieces of apple, plunge into plenty of hot fat, and fry

till a good colour. Drain on kitchen paper, pile high on a dish, and sprinkle

well with sugar; serve very hot.

Frying

Batter

1/4 lb. Flour--1/2d. 1/2

gill Tepid Water

White of Egg 1

dessertspoonful Oil--1d.

Total Cost--1 1/2d. Time--5

Minutes.

Sift the flour into a basin, pour over it the oil, then the water,

and beat into a smooth batter; stand away for an hour, if possible in a cool

place. Whip the white of the egg to a stiff froth, and stir it in, and it is

ready to use. This batter is useful for fritters and many dishes both sweet and

savoury.

If you're growing apples, watch out for

the BLACK SPOT!!! Truly: this must

prove it:

Crawford,

Frazer S. (Frazer Smith), d. 1890.

Report

on the Fusicladiums (Black spot, scab and mildew diseases) : the Codlin Moth,

and certain other fungus and insect pests attacking apple and pear trees in

South Australia. Adelaide : Published by

direction of the Hon. Commissioner of Crown Lands, 1886.

Did someone

feel we ought to collect all South Australiana? We do have a large collection,

yes, but most of it relates to the early explorers. ...That “Codlin Moth”

sounds threatening, too (those caps are not mine, no idea who catalogued it). Shades

of “Mothu” in that early post-Hiroshima Japanese horror movie.

“And is there honey still for tea?”

Purchas,

Samuel, d. ca. 1658.

A

theatre of politicall flying-insects : Wherein especially the nature, the

worth, the work, the wonder, and the manner of right-ordering of the bee, is

discovered and described. Together with discourses, historical, and

observations physical concerning them. And in a second part are annexed

meditations, and observations theological and moral, in three centuries upon

that subject. London : printed by R.I.

for Thomas Parkhurst, 1657.

Don’t get

over-excited, all you geographical-historical experts out there: This is not

the Samuel Purchas of "Hakluytus posthumus" or "Purchas his

pilgrims" fame. This Purchas is remembered precisely for this early work

on bees. I haven't been able to find out anything about him except that his

book describes him as “pastor of Sutton in Essex”.

Mrs Wicken doesn't seem to use honey in

her recipes, perhaps because it was still regarded as merely a spread. In fact,

a few years later in 1900 we find F.B. Guthrie (again), feeling the need to

advocate it as a food in an odd little 7-page pamphlet, the N.S.W Dept. of

Agriculture’s Miscellaneous publication

no. 386: Honey as food. Dr Muskett certainly mentions it as a spread

when he has a go at the Australian breakfast:

“...the monotony of the ordinary breakfast is

almost proverbial. With regard to the average household it is a matter of deep

conjecture as to what most people would do if a prohibition were placed upon

chops, steak, and sausages for breakfast. If such an awful calamity happened,

many the father of a family would have to put up with scanty fare. It is very

much to be feared that the inability to conceive of something more original for

the morning meal than the eternal trio referred to is a melancholy reproach to

the housekeeping capabilities of many. To read an account of a highland [i.e.

Scottish] breakfast, in contradistinction to this paucity of comestibles, is to

make one almost pensive. The description of the snowy tablecloth, the

generously loaded table, the delicious smell of the scones and honey, the

marmalade, the different cakes, the fish, the bacon, and the toast, is enough

to create a desire to dwell there for a very prolonged period. However, revenons à nos moutons; this has been

adverted to, not so much with the idea of urging people to copy such an

example, because expense would render it an impossibility, but to try and

awaken a determination to make more variety at the breakfast table.”

He wasn’t criticising

the deleterious affect on the cholesterol count, because his next para is an

encomium of saturated fats, in particular butter. Ice should be cheaper so that

even the “mass of the people” can afford a “very small and suitable ice chest”

to store their butter in.

He goes on: “Not only is this fatty

breakfast a necessary feature in the diet of everybody, particularly of the

young and growing population, but it is likewise a most important matter with

all brain workers. If the business or professional man can put in a liberal

breakfast, consisting largely of butter, fat bacon or ham, he can go on all day

with a feeling of energy and buoyancy. It is in this aversion to fatty matter,

in any shape or form, that the bilious and dyspeptic are so fearfully handicapped.”

Times have changed, all right: of late years Julia Child has been criticised

for using butter and cream. But human nature doesn't change with the fads: the

dietary-conscious were just as manic in the late 19th century as they are

today!

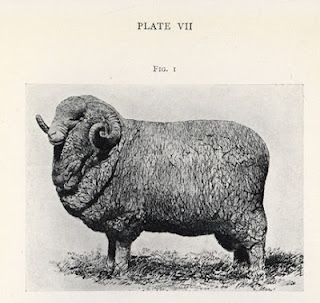

And Revenons

à nos moutons

|

| Merino sheep from Lydekker's The sheep and its cousins |

Sheep form an important, nay dominant,

motif in the earlier agricultural literature of Australia, but most of the

works we hold seem to relate to the wool industry rather than the food side.

Quite possibly the meat was taken so much for granted that it wasn’t worth

mentioning. Those breakfast chops that Muskett criticises would undoubtedly

have been sheep meat. But they would have been mutton, not lamb: our modern

lamb wasn't common until the post-war period, according to my friend Max, who

grew up before World War II. A couple of the RGSSA’s books on sheep are:

Australian sheep husbandry : a handbook of the breeding and treatment of sheep

and station management. With concise instructions for tank and well-sinking,

fencing, dam-making &c., by Albert Stapleton Armstrong and G. Ord

Campbell. (Melbourne : G. Robertson, 1882);

|

| "Novel wire strainer" from Australian sheep husbandry |

and: Our wool staple, or, A history of

squatting in South Australia, by W.R.L. (Adelaide : John Howell, 1865).

The latter is only 44 pages, but it's interesting that a history should already

be being written and that the word “squatting” was already in use.

19th century non-fiction was

characterised, it seems to me, by the compendious work. Everything that could be

said on a subject was said. And everything had to be understood in its place in

the scheme of things. The 18th century is traditionally seen as the age of the

great classifiers, taxonomists, if you like, such as Linnaeus, but I've always

felt that the trait was even more pronounced in the 19th. Possibly even Darwin

is symptomatic, but I'm not talking about him so much as the men like Melvil

Dewey, the obsessive inventor of the Dewey Decimal Classification scheme that’s

been the curse of libraries ever since. (Now I come to think about it, Mrs Beeton’s

The

book of household management (1861), is an example of the syndrome, and

so is her hubby’s work that the RGSSA holds: Beeton's dictionary of universal

information : comprising geography, history, biography, mythology, Bible

knowledge, chronology, with the pronunciation of every proper name (1859);

presumably the pair of them had their heads down at their desks all day!) A

terrific amount was published during the 19th and early 20th centuries in the

animal husbandry area attempting to describe all the members of whatever-it-was

fully, and sheep are no exception. We’ve got Richard Lydekker’s The

sheep and its cousins (London, Allen, 1912) “with 61 illustrations”,

which is a prime example of the type. I mentioned him in the last posting, on

lizards. He wasn’t into animal husbandry himself, he was an eminent English

naturalist.

|

| Some more sheep breeds from The sheep and its cousins |

Youatt,

William, 1776-1847.

Sheep

: their breeds, management, and diseases ; to which is added, The mountain

shepherd's manual. London : Baldwin and

Cradock, 1837. (Library of useful

knowledge)

I hope they

did find it useful. That “mountain” bit doesn't augur well – oh, dear.

Mrs Wicken has a lot of recipes for

mutton, including many for “chops”, meat unstated. She doesn't have to specify

“mutton”: everybody would have known that was what she meant. Recipes for

larger cuts are also given. The following is a fairly typical recipe for a time

when in many households the fire was lit in the morning and the oven was on all

day. It very clearly derives from Mrs Beeton’s 1861 recipe of the same name:

there is little difference except that she used bacon instead of ham. Her total

cost was 5 shillings, a lot more than Mrs Wicken’s! Does this reflect the

ubiquitous presence of sheep in the colonies?

Braised

Leg of Mutton

1 Leg of Mutton--1s. 3d. 1

Rasher of Ham--2d.

1 fagot of Herbs; 20 Peppercorns--1/2d.

1 1/2 oz. Butter--1d.

2 Carrots; 1 Turnip; 1 Onion; 1 quart Stock--1d.

Total Cost--1s. 7 1/2d. Time--Four

Hours.

Put the butter into a saucepan, and when it is dissolved put in

the mutton and brown it all over; then lay the ham and vegetables round it,

pour in the stock, and bring it to the boil. Cover down closely, and stand the

saucepan in a moderate oven where it will cook slowly. If the braising is being

done by a coal fire the lid of the stewpan may be reversed and some hot coals

placed in it; these will want renewing from time to time. In any case cook very

slowly, then dish the meat, strain the gravy, remove the fat carefully, and

boil to a sort of half glaze; pour round the dish, serve with julienne or plain

vegetables.

Taming the Savage Beasts

Of course to get ’em on the tables of

the nation, you had to get them out here and get them to thrive. Colonial

literature is thus full of works on “acclimatisation” –bringing alien plants

and animals out to a country which is almost wholly unsuitable for them and

expecting them to thrive. No wonder the farmers still complain about droughts

and floods. We’ve got umpteen reports of the various societies involved

(“Acclimatisation Society” in Victoria and New South Wales; “Acclimatization

Society” in South Australia). Everything that walked or grew and could be eaten

was pretty well covered by these societies and the many other advocates of the

practice: here’s just one on plants, by one of the better-known names:

Mueller,

Ferdinand von, 1825-1896.

Select

extra-tropical plants, readily eligible for industrial culture or

naturalisation, with indications of their native countries and some of their

uses. New South Wales ed. (enl.). Sydney : T.

Richards, Govt. Printer, 1881.

It's another compendious work: over 400

pages.

In case you were in doubt as to what

you might raise out here in the way of meat-bearing animals, P.L. Simmonds was

on the job, too, with his The animal food resources of different nations : with mention of some of the special dainties of

various people derived from the animal kingdom (London : Spon, 1885). It’s over 400 pages, as well!

“There’s nothing for it, chaps, we’ll have to eat the camels.”

It wasn't funny at the time, of course.

Warburton’s party of explorers nearly died in Central Australia. We have several

publications relating to the expedition; this is his own account, published in London:

Warburton,

Peter Egerton, 1813-1889.

Journey

across the western interior of Australia.

London : Sampson Low, 1875.

In 1872

Warburton was commissioned to lead an expedition across the Great Sandy Desert

in the interior of Australia. They had 17 camels and enough supplies for six

months. They left Alice Springs in April 1873: it was no longer full summer but

in the Outback it was still searingly hot, with drought conditions. Food ran

out and they had to eat some of the camels. Warburton got out, but he was blind

in one eye and too weak to walk; it was thanks to his Aboriginal companion

Charley that he survived this first crossing from the centre of Australia to

the west.

When in Doubt, Hang the Cook!

If food can save your life, it can also

be a weapon. This final work is one of the very many that the Royal

Geographical Society of South Australia holds which document the story of the

British in India; I've mentioned some of them in a previous blog. This book

tells the story of “Nikal Seyn”, one of the most colourful characters of the

period – and there were quite a few of them!

Trotter,

Lionel J. (Lionel James), 1827-1912.

The

life of John Nicholson : soldier and administrator, based on private and

hitherto unpublished documents. London : T.

Nelson, [1908]

Nicholson was

an Army officer of the East India Company who rose to be a brigadier-general –

a rise due solely to his capabilities and bravery, certainly not to any

boot-licking of his superior officers. He was known as the hero of Delhi to the

British public after he successfully planned and led the storming of Delhi in

1857 during the Sepoy Rebellion (the “Indian Mutiny”). He was wounded and died

some days after the battle. Many stories were told about him; this is typical

of the man. It was during the mutiny but things were calm enough for the

British officers to be waiting for dinner in their mess tent. Nicholson walked

in, cleared his throat and said: "I am sorry, gentlemen, to have kept you

waiting for your dinner, but I have been hanging your cooks." He’d heard that the soup had been poisoned –

the cooks of course were all Indians. They refused to taste it so he force-fed

it to a monkey, which dropped dead. So he hanged the cooks from a tree.

Shouldn’t it be the fate of all bad

cooks? I certainly feel it should, as I shudder and turn off those ghastly

cookery efforts on Australian TV.

So thank you, dear Julia Child, for

reminding us all that great cooking is possible and that good food can be

wonderful. Happy birthday.