AFGHANISTAN

&THE BRITISH RAJ AT RGSSA:

THE

FIRST "AFGHAN WAR"

Continuing the theme of Afghanistan. (See the May 2013 posting

for the first entry.) The Afghanistan exhibition curated by the Royal

Geographical Society of South Australia is about to travel to Whyalla. It

offers a unique opportunity to view some of the RGSSA's oldest books with links

to Central Asia and the Islamic civilisations, plus interesting artefacts, 19th-century

works of travel and exploration, and a selection of books, articles and

photographs relating to the Afghan cameleers who helped to open up Australia's

Outback.

The

blog is focussing on the books which give firsthand accounts of Afghanistan as

it was gradually and very painfully revealed to the West during the 19th

century.

The

First Afghan War, 1839-1842

The

First Afghan War, as the British called it (First Anglo-Afghan War, sometimes

called "Auckland's Folly"), was fought against Afghanistan by the

forces of British India, the Army of the East India Company, from 1839 to 1842.

It effectively ended with the one of the greatest disasters in British military

history: humiliatingly, not a pitched battle, but the ill-conceived and

appallingly badly managed retreat from Kabul. 4,500 British-led Indian soldiers

and 12,000 camp followers died.(1)

Prelude to War: "Bokhara" Burnes

By the

1830s Russian expansionism led the British to fear a possible Russian invasion

of India by way of Afghanistan. The British government therefore decided to

send an envoy to Kabul to form an alliance with Afghanistan's Amir Dost

Mohammad Khan against Russia. "Whoever they chose to lead such an

expedition would have to be a man of exceptional qualities; the endeavour, and

its dangers, would be the equivalent of a pioneering trek to the South Pole, or

the first flight to the Moon. The man they chose would need to be able to

withstand mountain passes and deserts, the threat of bandits, of being held

hostage or sold into slavery. More than this, he needed to be an expert in

languages, to possess an intimate knowledge of native culture, to have a gift

of affability, of making friends in difficult circumstances, and above all to

be observant: a sponge for current and reliable information, that might be

brought back and presented to the government in Delhi as it pondered its

policy. Fortunately for them, the hour presented the man: the one to undertake

this task would be Lieutenant Alexander Burnes."(2)

|

| "Bokhara" Burnes in the costume of the country |

It was

this Scottish soldier's first great expedition that earned him the nickname

"Bokhara Burnes":

Burnes, Alexander, Sir, 1805-1841.

Travels into

Bokhara : being the account of a journey from India to Cabool, Tartary and

Persia ; also, Narrative of a voyage on the Indus, from the sea to Lahore, with

presents from the King of Great Britain, performed under the orders of the

supreme government of India, in the years 1831, 1832, and 1833.

London : J. Murray, 1834. 3 v.

Burnes

had joined the Army of the East India Company as a lad, and once in India

showed extraordinary abilities, earning rapid promotion. He also, remarkably

for a British officer, learned Hindustani and Persian. He had been serving in

"Kutch" or "Cutch" (Kachchh), in western British India when

in 1831 he was appointed to lead a British party to Lahore, in the

north-eastern Punjab in what is now Pakistan, the ostensible reason for the

trip being to take a gift of horses from King William IV to Maharajah Ranjit

Singh.(1) Lahore was not under British rule: it was then the capital of the

powerful Sikh Empire, and Ranjit Singh was an important and influential ruler.

Lahore lies on the Ravi river, which flows west and then south-west in the

Punjab, joining the Chenab River, a tributary of the Sutlej, and thence of the mighty

Indus.

The

Indus "had not been navigated by Westerners since the days of Alexander

the Great; knowledge of it was scanty, and as with Afghanistan, the government

in Delhi was conscious it needed to know more about the territories beyond its

borders."(2) It would be a river journey of over 1,000 miles. Burnes

carried out the mission "in an exemplary fashion, collecting scientific

and cartographic data on the one hand, whilst also using his diplomatic talent

to maintain good relations with the tribal chieftains and nobles in the regions

through which he passed—all suspicious of the motives of the explorer."(2)

His book gives a unique account of the opulence of court life under Maharajah

Ranjit Singh.

During this trip he met the deposed Afghan

ruler Shah Shuja (or Shuja Shah) Durrani at the British station of Ludhiana. Significantly,

Burnes didn't think much of him; he wrote: "I do not believe that the Shah

possesses sufficient energy to seat himself on the throne of Cabool; and that

if he did regain it, he has not the tact to discharge the duties of so

difficult a situation"(2). Truer words were never written. The British

authorities' misguided reinstatement of Shah Shuja was to lead to their

crushing defeat in the First Afghan War.

Mission to Afghanistan

The

expedition to Bokhara (Bukhara) was a great success and led to Burnes's next

appointment, the mission to Afghanistan. His posthumously published account is:

Burnes, Alexander, Sir, 1805-1841.

Cabool : being

a personal narrative of a journey to, and residence in that city, in the years

1836, 7, and 8.

London : J. Murray, 1842.

After

the success of his venture up the Indus, the organisation of this second

mission was left up to Burnes. Both his own experiences and the example of

earlier European travellers to Afghanistan decided him to travel light, with no

display of either military power or wealth to incite an attack. He took only

three companions.(2) On his way through the Punjab he again called in at

Lahore, where he encountered a Frenchman, a "M. Court" who had come

over from Persia by way of Afghanistan. His advice about the safest way to

travel in the area prompted Burnes to dress in the local Afghan clothes and get

rid of his European tents, beds, chairs and so forth. As a result, he made it

through safely. It was not to be the marauding tribesmen who would be

responsible for his death in the country, but the stupidity of his military

superiors.

Burnes's wonderfully detailed account of

his journey, encompassing Jalalabad, Kabul, Bamiyan, Kunduz, Mazar-i Sharif and

much more gives an astoundingly unprejudiced and appreciative picture of all he

observed: the way of life, the natural features, the architecture, the wild

flowers in bloom on the hills and the formal gardens of the towns, and all the

local variations in religious observances and beliefs. He actually discussed

theology with the locals, in spite of M. Court's warning that it was a risky

topic. "Most important of all, he was able to understand the contemporary

politics of the country, by meeting and conversing with many of the chiefs and

leading men. ... With his characteristic charm, he was able to form close

relations with many members of the ruling Barakzye family in Peshawar and

Kabul".(2)

The Amir Dost Mohammad Khan

Of

these the most important was the Amir Dost Mohammad Khan (1793-1863), who had

become Amir of Afghanistan in 1826 after the decline of the Durrani dynasty and

the exile of Shah Shuja Durrani to the Punjab. Burnes discovered that he was a

highly intelligent man with an active mind, and their wide-ranging discussions

led him to the conclusion that "Dost Mohammed was the only person with the

acumen and vigour to re-unify the Empire of Afghanistan."(2) The Amir was

willing to become an ally of the British and Burnes realised that with only a

little help he would be the man to help prevent Russian encroachments into

northern India.

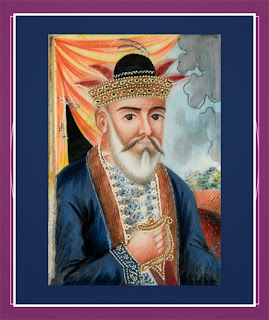

|

| The Amir Dost Mohammad Khan in later life |

Tragically, as it would turn out, Lord

Auckland, the Governor-General of British India, ignored Burnes's

advice—largely, it seems, because Dost Mohammad wanted British help to regain

Peshawar, on the north-West Frontier, which the Sikh Empire under Ranjit Singh

had seized in 1834.(3) Thus "Auckland's Folly".

British Reinstate Shah Shuja as Amir, & Advance into Afghanistan

|

| The reinstated Shah Shuja holds court |

Taking

the advice of Sir William Hay Macnaghten instead, Auckland decided to reinstate

the deposed Shah Shuja Durrani as Amir. Troops of the Army of the East India

Company marched into Afghanistan in March 1839, reaching Kandahar on 26 April. Shah

Shuja was proclaimed as ruler, and the deposed Dost Mohammed took refuge in the

mountainous Hindu Kush.(3)

Eye-Witness Accounts of the First Afghan War

What

was it really like in Afghanistan for the British during the First Afghan War?

We have several books which tell us. Two are by husband and wife. Sir Robert

Sale, one of the British commanders, produced a volume of lithographs:

|

| Sir Robert Sale |

Sale, Robert Henry, Sir, 1782-1845.

The defence of

Jellalabad /

by Sir R.H. Sale ; drawn on stone by W.L. Walton.

London : Published for the proprietor by

J. Hogarth ..., [1846?]

Sale's

wife, Florentia, Lady Sale, wrote more fully of her Afghanistan experiences:

Sale, Florentia Wynch, Lady, 1790-1853

A journal of

the disasters in Affghanistan, 1841-22.

London, J. Murray, 1843.

When the

First Afghan War began, Colonel Sale was assigned to the command of the 1st

Bengal brigade. He reached Kandahar in April 1839, and in May occupied the

Heart plain. Heading for Kabul, the British stormed the city of Ghazni,

"Sale in person leading the storming column and distinguishing himself in

single combat."(4) They then reached Kabul easily. Sale was awarded the

KCB and promoted to major-general. "He was left, as second-in-command,

with the army of occupation, and ... conducted several small campaigns ending

with the action of Parwan which led directly to the surrender of Dost Mahommed

Khan."(4)

The British forces were now in cantonments,

and everything seemed so peaceful that many of their families came to join them

in Kabul, including Lady Sale and her daughter, also married to a serving

officer. Lady Sale's journal gives a vivid picture of the carefree, elegant—and

in some cases sybaritic—life of the British in Kabul.

Burnes in Kabul

Alexander

Burnes at this time had become the political agent in Kabul. It's an

interesting sidelight on his character—and perhaps helps to clarify the

readiness with which he took to the charming and decorative Afghan costume—that

the life he led there, far from that we might expect of a stern Scottish

soldier, was little short of hedonistic!

|

| "View of Cabool, from the East", plate facing p.234, from Burnes's Cabool; from an original sketch of Kabul "by Capt. H. Wade, of H.M. 13th Regiment" |

Afghan Uprising

The

Afghans had never truly accepted either the presence of the British or their

puppet ruler, Shah Shuja, and after a while hostilities flared. The Afghan

tribes flocked to support Dost Mohammad's son, Akbar Khan. Burnes had at one

stage left Afghanistan but he was back again: all his advice was ignored and

the British authorities insisted on supporting Shah Shuja instead of Dost

Mohammad Khan.

By the time Sale's brigade was ordered to head

to Jalalabad to clear the vital line of communications to Peshawar on the

North-West Frontier (near the end of the Khyber Pass, close to the

Indian-Afghan border), the situation was very dangerous indeed—not least for

the British forces in cantonments outside Kabul, in a position which would be

nigh impossible to defend.

Murder of Burnes

Violence

flared in Kabul and Afghan rebels, led by Akbar Khan, murdered Burnes. Hedonist

he might have been, but the calmness with which he continued at his post, and

the ferocity with which he fought after the killing of his political assistant,

Major William Broadfoot, killing six assailants before meeting his own fate, won

him a heroic reputation.

Chicanery and Cover-Up

It

seems incredible that all Burnes's excellent advice on tactics was ignored by

the British authorities, just as his original advice against supporting Shah

Shuja had been. In fact, those to whom he reported behaved shockingly badly and

did not pass on all his advice: there was chicanery during his period in Kabul

and then a cover-up: "It came to light in 1861 that some of Burnes'[s]

dispatches from Kabul in 1839 had been altered so as to convey opinions

opposite to his, but Lord Palmerston refused after such a lapse of time to

grant the inquiry demanded in the House of Commons."(1)

Sale Takes Jalalabad

On his

way to "Jellalabad", that is, Jalalabad, Robert Sale received the

news of Burnes's death. He was ordered to return to Kabul as fast as possible,

but using his better judgement, decided not to: "suppressing his personal

desire to return to protect his wife and family, he gave orders to push on."(4)

They reached Jalalabad, a city in eastern Afghanistan at the junction of the

Kabul River and Kunar River, to find a rebel force installed and the way back

to India blocked.

After severe fighting Sale took Jalalabad

on 12 November 1841. Its defensive walls were half-ruined: he immediately set

about making it fit to withstand a siege. His volume of lithographs includes

his detailed drawings of the improvements he made to the defences. (I haven't

digitised any because a small reproduction won't give you any idea of how

impressively detailed they are and how careful a tactician he must have been.) On

7 April 1842 the beleaguered garrison "relieved itself by a brilliant and

completely successful attack on Akbar Khan's lines."(4) General Pollock eventually

arrived with a relieving army, but Jalalabad no longer needed them, thanks to

Sale.

A detailed history of this episode is given

in:

Gleig, G. R. (George Robert), 1796-1888.

Sale's brigade

in Afghanistan : with an account of the seisure and defence of Jellalabad.

London ; John Murray, 1861

If the rest of the British forces could get

as far as Jalalabad, their way back to the Frontier and thence the safety of

India would be relatively clear.

Disastrous Retreat of British from Kabul

In the

meantime the British forces in Kabul had fled, with amongst them Florentia,

Lady Sale, with her daughter and son-in-law. Lady Sale was known in her

lifetime as "the Grenadier in Petticoats"(5): she travelled the world

with her husband on all his postings, but it was perhaps not these travels, as

varied as any soldier's of the time, which earned her the nickname, but her

determination and grit—as her portrait taken in later life attests!

|

| The "Grenadier in Petticoats" |

Her

journal offers a stringent description of the complete muddle and panic amongst

the British in Kabul when the rebellion broke out. She "gives us a full

and vivid picture of events", reporting on "the anxiety and ineptitude

of Shah Shuja; [and] the procrastination and confusion of command, as men are

readied to take action and told to stand down, marched out of the gates, and

told to return. She does not soften her words in the portrayal of characters,

or dissemble to preserve the good name of anyone".(2)

Panic Leads to Massacre

What

followed this panic was the disastrous British retreat from Kabul in the icy

Afghan winter of 1841/1842. At the beginning of 1842 an agreement was reached with

the rebels for the safe exodus of the British garrison and its dependants from

Afghanistan.(6) They were about 16,500 souls, only about 4,500 being military

personnel and over 12,000 camp followers. Most of the troops were Indian units,

plus one British battalion, the 44th Regiment of Foot. It was ferociously cold:

the worst time imaginable to try to get a large contingent, encumbered as they

must have been by the cook-waggons and all the camp followers' baggage, through

the mountains of Afghanistan.

They were ambushed in the snowbound passes

by Akbar Khan's supporters, with huge slaughter in what was more or less a

running battle, culminating in a massacre at the Gandamak Pass. Fewer than

forty men survived the retreat from Kabul. A handful of British were taken

prisoner. Only one Briton reached the relative safety of the garrison at

Jalalabad, a Dr. William Brydon.(6) It was one of the bitterest episodes in

British military history.

British Hostages in Afghanistan

|

| Portrait of an Afghan, said to be Akbar Khan, by Vincent Eyre |

Lady

Sale's party—she, her daughter (Mrs Sturt), and other members of British

officers' families—were lucky to be taken prisoner at the beginning of 1842

rather than slaughtered along the way. They were eventually rescued, later in

1842, and got back to India.

Another

account of the British hostages' captivity in Afghanistan is given in:

Eyre, Vincent, Sir, 1811-1881

The military

operations at Cabul, which ended in the retreat and destruction of the British

Army, January 1842 : with a journal of imprisonment in Affghanistan.

London : J. Murray, 1843

Vincent Eyre (later Sir Vincent) was one of the many young Englishmen

who joined the East India Company's army: in his case, the Bengal

Establishment. After 10 years' service he was appointed "Commissary of

Ordnance" to the Kabul field force, in 1839. Like the Sales, his family

went out to Afghanistan expecting the comfortable life of a peaceful posting.

Eyre and his family were also captured during the Afghan uprising led by Akbar

Khan in January 1842. Ironically, it was their months in captivity which saved

their lives. Besides writing a diary of his experiences, Eyre, who was a

considerable artist, also sketched the personalities—officers, women, and even

enemies—whom he met. They are charming works, with a great delicacy of touch.

|

| Two of Eyre's sketches of the Kabul prisoners |

The

manuscript of the diary is said to have been smuggled out to a friend in

British India. It was published in England as Military Operations at Cabul in 1843 and immediately ran into

several editions. The colour lithographs of his portraits were sold as a set

under the title: Portraits of the Cabul

Prisoners. The lucky Eyres, like Lady Sale, were later rescued. Eyre went

on to a distinguished military career.

End of the War

British

morale was greatly shaken when reports of the disastrous retreat from Kabul

began to filter through. In September 1842 the British forces retook Kabul and

freed the prisoners. Reprisals included great destruction and terrible, vicious

slaughter of civilians. The British then withdrew from Afghanistan through the

Khyber Pass. Dost Mohammad was released and was able to re-establish his

authority in Kabul.(6)

What Would Happen Next?

With

British influence west of the Khyber Pass waning the way was left open for

Russian influence: an opportunity of which the Russian Bear did not fail to

take advantage. We see, in the 30 years following the First Afghan War, steady

Russian encroachment on Afghanistan. By 1873 "Russian control ... extended

as far as the northern bank of the Amu Darya."(6)

Above: Sketch map of the

route of the mighty Amu Darya, the largest river of Central Asia (known in the

19th century as the Oxus River), from its origin in the lofty Pamirs to the

Aral Sea. It forms the northern border of modern Afghanistan. By 1873 most of

the countries of modern Central Asia (shown in pink) were under direct or

indirect Russian control.

References:

(1) "Alexander Burnes", Wikipedia

(2) Bijan Omrani. "Will we make it to

Jalalabad?"

(3) "Dost Mohammad Khan", Wikipedia

(4) "Robert Sale", Wikipedia

(5) "Florentia Sale", Wikipedia

(6) "First Anglo-Afghan War", Wikipedia

--

This post was researched and created by Kathy Boyes