AFGHanistan & THE British RAJ AT RGSSA:

The Second "Afghan War", 1878-1880

AND ITS AFTERMATH

The

Second Afghan War (or Second Anglo-Afghan War) was the second major conflict

between the British and Afghanistan. It took place from 1878 to 1880 and

incorporated not only a crushing defeat for the British and a resounding

victory for the Afghans at the Battle of Maiwand, but also a much-celebrated

victory for the British at the Battle of Kandahar, or Relief of Kandahar, which

ended the war in 1880. The British were enabled to claim over-all victory but

they never managed to establish British rule in Afghanistan.(1)

The Second Afghan War was split into two

campaigns or phases, the first taking place from November 1878 to May 1879, and

the second lasting from September 1879 to September 1880 (2). The forces

involved on the British side were now under the direct control of the British

Government, which had by this time taken over the rule of British India from

the East India Company. As it had also taken over the old regiments, many of

the older men serving in the war had also seen service with the East India

Company’s Army.

Prelude to Conflict: British Lion Reacts to Advancing Russian

Bear

As

always with Afghan matters, the background to the conflict is complex. The

Russians were expanding into Central Asia. In the summer of 1878 "Russia

sent an uninvited diplomatic mission to Kabul."(1) The Amir of Afghanistan

at this time was Sher Ali Khan of the Barakzai dynasty, a son of Dost Mohammad

Khan. When the British demanded the Amir accept a mission from them as well, he

refused permission and threatened to stop any effort to send one. Nevertheless

the Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton, ordered a diplomatic mission to set out for

Kabul in September 1878. It was turned back on approaching the British India

end of the Khyber Pass. This triggered the war.

The First

Phase

Above: 45th Rattray's Sikhs with

prisoners from the Second Afghan War, 1878. “The three Afghan prisoners

captured in the advance through the Khurd Khyber are sitting in the centre of

the photograph, surrounded by Sikh guards. The 45th Sikh Regiment was raised in

1856 by Captain Thomas Rattray, and was popularly known as Rattray’s Sikhs. ...

The Regiment served in the Fourth Infantry Brigade, part of the Peshawar Valley

Field Force, during the Second Afghan War. The prisoners were lucky to have

survived because in the harsh conditions and terrain of the Afghan Wars no

quarter was given and prisoners taken, on both sides” -Wikipedia.

The

first campaign began in November 1878. The British sent in a force of about

40,000 troops, penetrating the country from three different points The major

battle of this period was the Battle of Ali Masjid. Much of the country was

successfully occupied by the British.

Treaty

On the

death of the Amir Sher Ali in February 1879 the British seized the opportunity

to make the Treaty of Gandamak with the new Amir, Sher Ali's son Mohammad Yaqub

Khan. The negotiator was Pierre Cavagnari, in spite of the name a British

officer and administrator who had seen service with the Army of the East India

Company.(3)

|

| Cavagnari sitting with a group of Afghan tribesmen |

The

treaty, signed in May 1879, ended the first phase of the Second Afghan War.

"According to this agreement and in return for an annual subsidy and vague

assurances of assistance in case of foreign aggression, Yaqub relinquished

control of Afghan foreign affairs to Britain. British representatives were

installed in Kabul and other locations, British control was extended to the

Khyber and Michni passes, and Afghanistan ceded various North-West Frontier

Province areas and Quetta to Britain. The British Army then withdrew." (1)

Uprising

As can

well be imagined, the Afghans were not satisfied with this state of affairs,

and there was an uprising in Kabul in September 1879. Cavagnari, who had been

given the post of British representative in Kabul, also receiving the Star of

India and a KCB, was killed along with the other European members of the

mission and their guards, members of The Guides, when he refused the Afghans'

demands.(3) This provoked the next phase of the Second Afghan War.

The Second

Phase

In the

second phase of the war Major General Sir Frederick Roberts "defeated the

Afghan Army at Char Asiab on 6 October 1879, and occupied Kabul." A

rebellion in December 1879 failed.

"Yaqub Khan, suspected of complicity in the massacre of Cavagnari and his

staff, was obliged to abdicate."(1)

British Install Abdur Rahman Khan as Amir

There

were several solutions the British considered but in the end they opted for

installing Abdur Rahman Khan, (more properly Abd al-Rahman Khan), a cousin of

Yaqub Khan, as Amir. The consequences of this decision, as we'll see when we

look at the aftermath of the war, were extremely significant.

Afghan Victory at Battle of Maiwand

At this

Yaqub Khan's brother, Ayub Khan, who had been serving as governor of Herat,

rose in revolt. In the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 he totally defeated

the British troops under General Burrows. It was "the biggest British

disaster, and the greatest Afghan victory" of the war.(2)

Ayub's next move was to besiege the

remainder of the British garrison at Kandahar. In response, on 8th August 1880

General Roberts set out with an army of 10,000 from Kabul to relieve

Kandahar—over 300 miles away.

The Relief of Kandahar

The

relief of Kandahar is one of the military exploits recounted in the book based

on Edmund Musgrave Barttelot's writings and published after his death by his

brother Walter:

Barttelot, Walter George, &

Barttelot, Edmund Musgrave, 1859-1888

The life of

Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, Captain and Brevet-Major Royal Fusiliers, Commander

of the Rear Column of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition : being an account of

his services for the relief of Kandahar, of Gordon, and of Emin, from his

letters and diary. 3rd ed.

London, R. Bentley, 1890

Barttelot

had a successful military career but his reputation in Britain was seriously

marred by his madness and resultant death in Africa. His name crops up in

several publications of the late 1880s and early 1890s about the Dark Continent

because he was one of the explorers in "Stanley's rear-guard", the

Rear Column of Henry Morton Stanley's "Emin Pasha Relief Expedition"

of 1887-1889. According to some accounts Stanley's own picture of this incident

was extremely prejudiced. Walter Barttelot's book was intended to defend his

brother's reputation.(4)

Several years before this tragic episode,

however, Edmund Barttelot was an officer with the 7th Royal Fusiliers in India,

and was thus amongst the troops who relieved Kandahar. "The march from

Kabul to Kandahar was quite a feat in that it moved so many men such a distance

and in a relatively short period of time. They marched through terrific heat

and dryness, not knowing what resistance they would meet on the way..."(2)

General Roberts's venture was, however, a resounding success. Kandahar was relieved:

"the day after Roberts arrived, on September 1st, he defeated Ayub Khan

and the Afghan army, effectively ending the conflict of the Second Afghan

War." (2)

A British Victory or Not?

With

the confirmation of the Treaty of Gandamak by the British Government's choice,

the Amir Abdur Rahman, the British retained control both of the territories

ceded by Yaqub Khan, and of Afghanistan's foreign policy, in exchange for

protection and a subsidy. They would no longer maintain a British Resident in

Kabul, it having at last dawned, after the successive murders of their

representatives during the First and Second Anglo-Afghan Wars, that this was

considered provocation by the Afghan people. This situation was generally depicted

in rosy terms by English writers, an attitude which is reflected in many modern

accounts, but this was largely spin. Maybe the advance of the Russian bear

towards the territory of the British Raj had been halted—but internal events in

Russia were fast overtaking Russian policies in any case.

|

| "The Khaiber Pass. A village in the pass belonging to independent Afghans, showing tower and fortifications", photograph by T.L. Pennell |

Aftermath oF War: The Reign of The Iron Amir

After

1879 the fate of Afghanistan was shaped by the new Amir, the British-appointed Abd

al-Rhaman Khan (or Abdur Rhaman, as contemporary accounts refer to him).

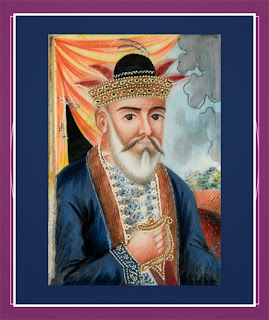

|

| The Amir Abd al-Rahman Khan |

The

Royal Geographical Society of South Australia holds several books about the

Amir. A close-up is provided by:

Gray, John Alfred, 1857-1929

At the court of

the Amir.

London : R. Bentley, 1895

John

Alfred Gray's personal account describes the court life in Kabul in the latter

part of the 19th century during the reign of the Amir Abd al-Rhaman Khan,

covering such diverse topics as "Life in Kabul"; "The Kabul

bazaars"; "Ethics"; "Afghan surgeons and physicians";

"Life in Turkestan"; "The birth of Prince Mahomed Omer";

"The rearing of the infant Prince"; "The Amir"; "The

Amir's conversation"; and "The Amir as an art critic". Dr. John

Gray was surgeon to the Amir for five years. He was only a young man when he

went out on his adventure to Afghanistan. Back in England he did a further a

medical qualification and settled down to a practice in the respectable London

borough of Ealing (5)—a far cry from the exotic opulence of the Amir's court!

Afghan Life in the Later 19th Century

|

| "A Cavalry Shutur-Sowar or Camel-Rider", photograph by T.L. Pennell |

Life for

most of the population was of course nothing like court life. It's not the

accounts of the explorers and soldiers, but those of the missionaries, which

afford us a view of how the ordinary people lived. During the 19th century

there was a stronger and stronger British missionary presence in the Indian

subcontinent, and by the later part of the century they had made tentative

inroads into Afghanistan—not an easy task on a merely physical level, when we

consider the terrain, and near to impossible on the theological level. Whatever

we may think today of these earnest proselytizers, they did make a genuine

contribution to the health and physical welfare of the people amongst whom they

lived. There are many testaments to such endeavours in the literature of the

British Raj and of the British Empire in general. One such in the RGSSA library

is:

Pennell, T. L. (Theodore Leighton),

1867-1912.

Among the wild

tribes of the Afghan frontier : a record of sixteen years' close intercourse

with the natives of the Indian marches. 5th & cheaper ed.

London : Seeley, Service & Co., 1913

Theodore

Leighton Pennell (1867-1912) was an English medical missionary during the 19th

century. His work took him over a wide stretch of the territory then known as

the Northwest Frontier of British India, in what is now Pakistan, and thence to

Afghanistan. His book Among the wild

tribes of the Afghan frontier abounds with descriptions of the lifestyles,

habits and customs of the Pushtun peoples of the area. Together with his

photographs of the daily lives of the people these accounts are the enduring

legacy of his work, and a valuable contribution to the social history of the

area.

|

| "Women going for water at Shimvah" |

Above is one of the few contemporary pictures

of women of the Frontier area; nearly all of the figure studies in the books on

Afghanistan and the Northwest Frontier in the RGSSA’s collection are of men.

Efforts

at conversion such as those of Pennell, nibbling away at the fringes of Afghan

territory, were never to lead to anything more. The Amir chosen by the British

was never going to allow his people to be converted—or, indeed, Westernised at

all.

The Iron Amir

Abd

al-Rahman Khan (or Abdur Rahman Khan), the British choice for Amir during the

Second Afghan War, was to reign successfully and firmly over Afghanistan until

his death in 1901, becoming known as "The Iron Amir."

|

| "Abdur Rahman, the late Amir of Afghanistan: drawing by Lady Helen Graham" |

Wheeler, Stephen, 1854-1937

The Ameer Abdur

Rahman.

London: Bliss, Sands and Foster, 1895.

(Public men of to-day)

Willcocks, James, Sir, 1857-1926.

From Kabul to

Kumassi : twenty-four years of soldiering and sport / by James Willcocks ; illustrations by

Helen Graham.

London ; Murray, 1904.

The

Amir was both ruthless and politically adept. Cruel episodes of genocide went

side-by-side with the cool-headed balancing of the opposing powers which

surrounded him in Central Asia. During his reign he completely consolidated his

position and gained dominion over the warring tribes of Afghanistan.

The results of their appointment were

doubtless not what the British had expected: far from being a puppet, the Amir

used the British government's annual subsidy of 1,850,000 rupees to import

munitions, and "availed himself of European inventions for strengthening

his armament, while he sternly set his face against all innovations which, like

Railways and Telegraphs, might give Europeans a foothold within his

country." He was a fervent believer in Islam, in 1896 adopting the title

of Zia-ul-Millat-Wa-ud Din ("Light of the nation and religion"); an

educated man, he published treatises on jihad.

(6)

It is perhaps not an exaggeration to say

that Amir Abd al-Rahman’s religious conservatism and fierce patriotism, both of

which prompted him to shun the West and its ways, in combination with the

militarism which had always characterised the Afghan dynasties, a tradition

which he continued and consolidated, moulded the Afghanistan of today.

Going

one step further, we might say that the current conflict in Afghanistan can be

traced back, not merely to the country’s tribal roots and endless dynastic quarrels,

but to the British choice of Abdur Rahman Khan as their preferred ruler during

the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

References

(1)

"Second Anglo-Afghan War", Wikipedia

(2)

"The Second Anglo-Afghan War, 1878-1880",

(3)

"Pierre Louis Napoleon Cavagnari", Wikipedia

(4)

"Edmund Musgrave Barttelot", Wikipedia

(5)

"[Obituary: Dr. John Gray]", British Medical Journal, 2 (3595), p.

1034 (Nov. 30 1929), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2452545/?page=1

(6)

"Abdur Rahman Khan", Wikipedia

--

This post was researched and created by Kathy Boyes